This post, written by Annaliese Jacobs Claydon and Kate Bagnall, was first published on the Everyday Heritage website on 18 September 2024.

It’s a chilly Friday morning in South Hobart, and Anna is looking for Chinese names in Tasmanian post office directories – the early-twentieth-century equivalent of the telephone book. It might sound like looking for a needle in a haystack, but in fact it’s just one of the steps in our research to uncover the ordinary lives and hidden histories of Chinese individuals, families and businesses in the island state.

For our Tasmanian case study, the Everyday Heritage team in Tasmania is using simple yet powerful, freely available digital tools to help paint a historical picture of Chinese communities in virtually every corner of Tasmania.

While some part of Tasmania’s Chinese history is quite well known, we are focusing on the mundane, the everyday, and the commonplace to tell stories of how ordinary people built their lives in Tasmania at a time when Chinese migration was restricted and anti-Chinese sentiment was common.

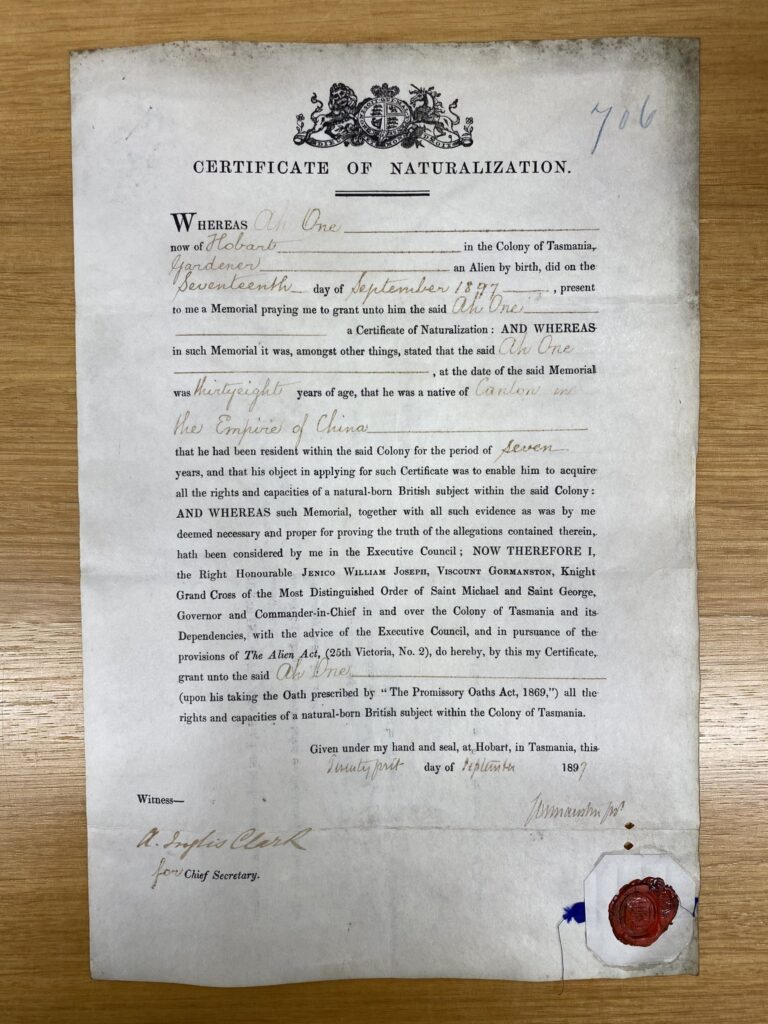

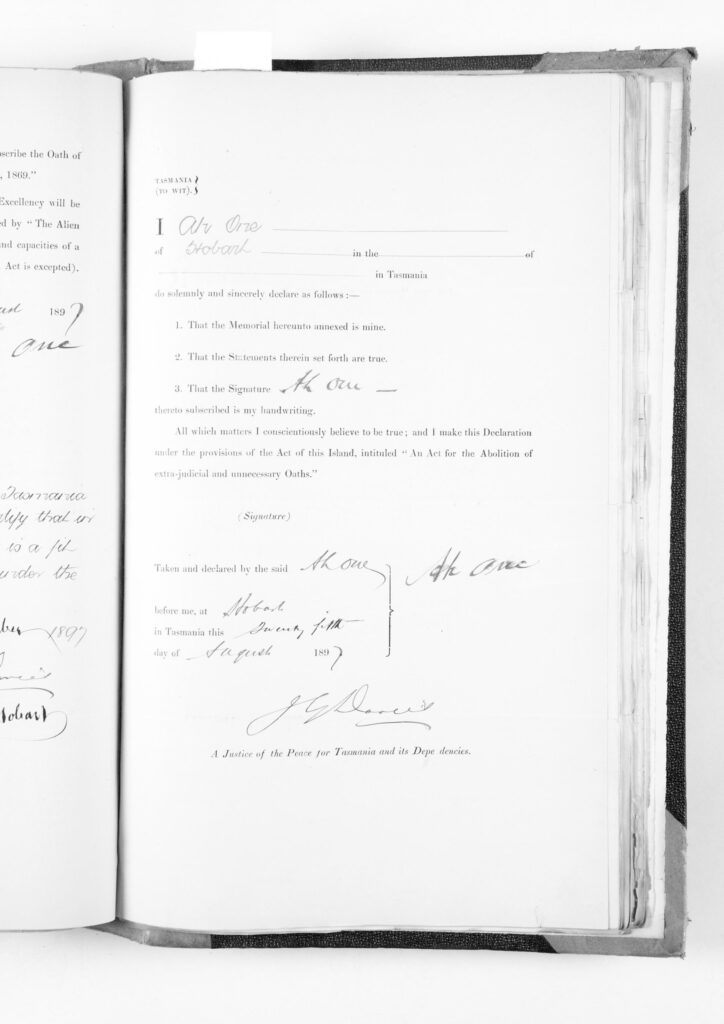

Our first step was to figure out who we were looking for – to build a list of names and occupations. We started with a preliminary list of Chinese Tasmanian residents gleaned from archival indexes and databases from the Tasmanian Archives and the National Archives of Australia. Naturalisation and alien registration records provided a rich beginning, but we also want to find people moving in and through the state alongside those who settled long term.

Anna spent several months scouring the digitised newspapers in Trove for articles that could help generate further names and unexpected places. Good search strategies are necessary to weed out Tasmanian stories from mainland articles republished in Tasmanian newspapers, and to identify articles that mention a specific person, event, and/or place (and ideally all three).

In order to manage the data, we are using Zotero – a bibliographic software that can grab metadata and images from a wide variety of sources, including Trove’s digitised newspapers and many library and archival collections. Once in Zotero, you can highlight, tag, and annotate the records.

The tags are especially important for our project. They function as a growing, searchable index to the material, but they will also be used in the next stage of the project, in which we will digitally map Chinese Tasmanian individuals, families, communities, and businesses over time.

Our research in the digitised Tasmanian newspapers in Trove has not only found some fascinating stories, it has also generated a long list of names and addresses across the state, from Southport in the south, to Fingal in the north-east, to Strahan on the west coast.

Of course, this list from the newspapers is incomplete and problematic. For example, the English spelling of Chinese names varies widely, and newspaper articles tend to focus on burglaries, assaults, gambling, and alleged opium smuggling, capturing the ‘dog whistles’ of anti-Chinese sentiment but not the texture of everyday life.

How can we both acknowledge and filter out that noise?

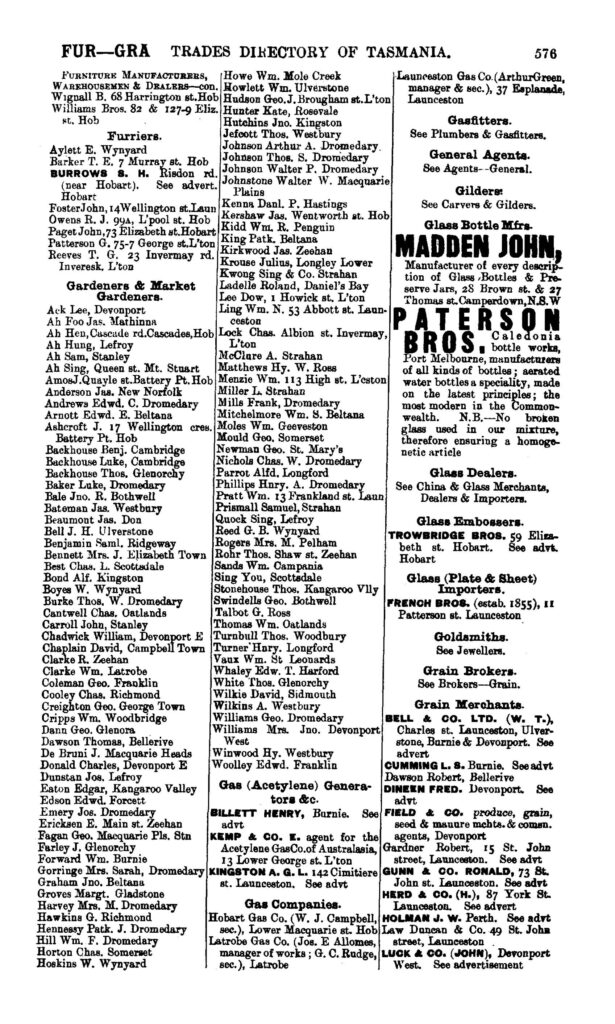

One way is through the post office directories, which provide names, businesses, street addresses and dates. Several years ago, Libraries Tasmania digitised their collection of Wise’s Post Office Directories from 1890 to 1948. As part of his GLAM Workbench, project team member Tim Sherratt has created an interface to the Tasmanian Post Office Directories that makes them searchable by keyword.

Focusing on the post office directories helps to compensate for the prevalence in the newspapers of crime and racial language. In the directories, you find fruiterers, market gardeners, launderers, fancy goods merchants, carpenters, and others, along with their locations.

Anna has been creating records of the ‘Chinese’ post office directory listings in our Zotero Group Library, tagging them with individual names, addresses, and occupations, and anything else that looks fruitful. She also spells out the common abbreviations for occupations and names – so ‘frtr’ is changed to ‘fruiterer’ and ‘gcr’ to ‘grocer’, while ‘Hy’ is changed to ‘Henry’ and ‘Jas’ to ‘James’.

Going through year by year, directory by directory, allows us to see continuity and change over time, growth and decline of neighbourhoods and discreet populations, and family networks. It can also turn up some quite interesting stories!

One is about ‘James Ah Foo, skin dealer, Fingal’ – who appears in a post office directory in 1921. ‘James Ah Foo’ shows up elsewhere, too – there was also a market gardener in Mathinna between 1904 and 1911 who listed his name as ‘Ah Foo’ but also called himself James Ah Foo.

Was this the same person? We’re not absolutely sure, but Anna thinks it’s likely. Newspaper accounts find James Ah Foo back and forth between Mathinna and nearby Fingal, sometimes the victim of crime, sometimes of circumstance, and sometimes falling afoul of the law himself.

Anna found James Ah Foo involved in a major conflagration in Mathinna in 1901, which started at the rear of C.J. Bailey’s butcher shop and extended to the Bulman Brothers general store. The fire spread and claimed two buildings owned by James Ah Foo, where Miss Fitzgerald ran the newsagency and Mr Dunn had a fruit stand.

Three years later, James Ah Foo was splitting his time between Mathinna and Fingal, where he prosecuted two men for stealing his skins. He was burnt out again in Fingal in August 1907 while he was on a visit back to Mathinna, and a year later, he was run over by his own bolting horse. Soon after the introduction of the Game Act, he was prosecuted for having excess kangaroo and possum skins out of season in 1909.

James Ah Foo was also fond of horse racing – at Avoca in 1918, he told a racing correspondent that:

he was 82 years and four months old, had been in Australia 61 years, during which time he had paid only one visit to China. He has been living at Fingal for 20 years, where he follows the calling of a skin buyer, and says he would sooner live in Tasmania than any other country.

Each of these newspaper articles documents one moment when James Ah Foo came to the attention of the public. The post office directory listings help place him in one of the locations where he lived and worked. Together, they help to illustrate his network of associates – his tenants, neighbours, and business partners, people with whom he had disagreements and with whom he was on good terms. Some were Chinese, but many were not.

Beginning with digitised archives, our research is starting to sketch outlines of dozens of everyday Chinese lives in Tasmania – each of whom left their mark on the island, its communities, and its histories.

Bio

Annaliese Jacobs Claydon is a researcher on the Everyday Heritage project and an Adjunct Researcher in the School of Humanities at the University of Tasmania. A historian of empire and exploration by training, she has also worked for many years as a public historian and an archivist.

Kate Bagnall is a social historian best known for her research on Chinese Australasian history. Kate is a Chief Investigator on the Everyday Heritage project and Senior Lecturer in Humanities (History) at the University of Tasmania.