This is the paper I presented at the 2018 Australian Historical Association conference, ‘The Scale of History’, held at the Australian National University on 2–6 July 2018. I spoke alongside Sophie Couchman and Emma Bellino in a panel we put together on ‘National belonging and individual lives’:

- Kate Bagnall: Chinese Australian families and the legacies of colonial naturalisation

- Sophie Couchman: New questions about the enlistment of Chinese Australians during World War I

- Emma Bellino: ‘Australian girl became an alien’: Reporting married women’s nationality.

Sophie spoke about the disconnect between World War I enlistment regulations and practice in relation to Chinese Australians, while Emma spoke about press reports of marital denaturalisation in Australian newspapers from the 1920s to 1940s.

Abstract

In 1888 the Australian colonies came together to implement uniform laws to restrict Chinese immigration, leading eventually to the enactment of the Immigration Restriction Act after Federation in 1901. Alongside immigration restriction, after 1888 four Australian colonies also prohibited Chinese naturalisation, by law in New South Wales and by policy in Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. The federal Naturalisation Act of 1903 similarly prohibited Chinese naturalisation. Before these restrictions were introduced, however, thousands of Chinese men in Australia became British subjects through naturalisation, nearly 1000 in New South Wales alone. In this paper I consider the legacies of colonial naturalisation in the lives of Chinese migrants and their families in the 1890s and after Federation, particularly concerning mobility and residency rights. I argue that it is through the stories of individual lives, revealed in the press and in government case files, that we can best understand the ways that naturalised Chinese Australians and their children contested discrimination and asserted their rights as citizens.

Introduction

In early January 1889, the Ah Ket children of Wangaratta, Victoria, were stopped at the border of New South Wales. Fourteen-year-old Matilda, together with her three younger siblings aged thirteen, ten and eight, were travelling to the small town of Gerogery, north of Albury, to visit their married sister Rose. On arriving by train at Albury, however, the Ah Ket children were prevented from crossing the border by the Sub-Collector of Customs. The reason? Because they did not hold naturalisation papers. Confronted by the news that they would not be allowed to continue their journey, Matilda stood her ground, declaring that they had been born and educated at Wangaratta; that they were the children of a Chinese interpreter, Mah Ket; and that as ‘native-born children’ they were free to go anywhere in Australia. The Sub-Collector was unconvinced, and so sent them back home to Victoria by the same train. Their father, and the good people of Wangaratta, were appalled by the Customs officer’s actions. Mah Ket put the matter in the hands of a solicitor, and on 19 January 1889, the Wangaratta correspondent to the Melbourne Leader wrote an impasssioned piece on the family’s behalf:

The children whose liberty is so circumscribed are natives of Wangaratta, very intelligent and Christian; and speak better Queen’s English probably than some of the honorable gentlemen who made the law under which they are treated as aliens. It has been determined that for the peace and prosperity of the colony, Chinese immigration shall be restricted. But here were no aliens, but the most peaceful and defenceless of Australians – of like speech, education, religion and affections.

The Act under which the Sub-Collector of Customs stopped the children was the NSW Chinese Restriction and Regulation Act, passed six months earlier, in June 1888. This Act, and others introduced around the Australasian colonies, were the result of growing concerns over Chinese immigration.

One of the children stopped at the NSW border that summer’s day in 1889, thirteen-year-old William Ah Ket, grew up to be Australia’s first Chinese barrister. Educated at Melbourne University and admitted to the bar in 1903, Ah Ket had a distinguished legal career in which he actively campaigned for the rights of Chinese in Australia. He appeared before the High Court, represented Australian Chinese at the opening of the first Chinese parliament in Peking in 1911, and was Acting Consul for China in Australia in 1913–1914 and 1917. He was also a husband and father to two daughters and two sons.

This paper considers nationality, naturalisation and colonial mobility through the lens of Chinese Australian families like the Ah Kets. Mah Ket, the Ah Ket children’s father, was not naturalised, but this should not have mattered when the children tried to cross into New South Wales. Young Matilda was right – as native-born British subjects, the NSW Chinese Restriction Act should not have applied to them. Yet, the fact that they were turned back illustrates the ambiguity with which immigration restriction laws were applied to native-born and naturalised Chinese British subjects in Australia and New Zealand. The law stated what it stated, but it’s truth also lay in the way that it was interpreted and applied – whether that was at the border, in a bureaucrat’s office, in a magistrate’s court or in the High Court.

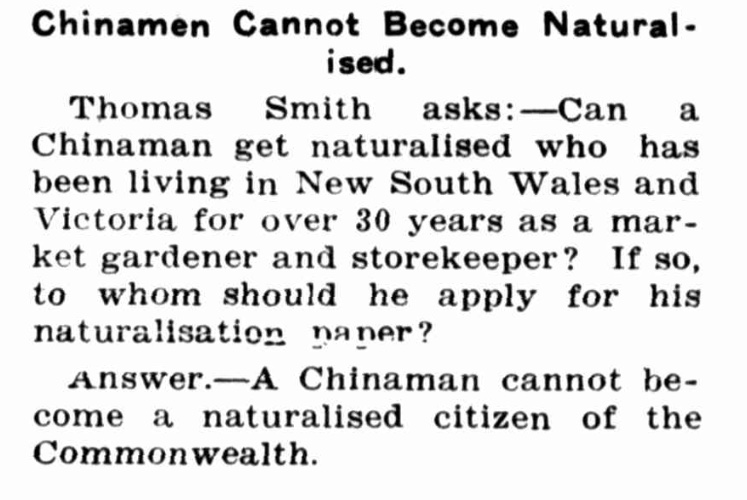

Prohibition of Chinese naturalisation formed part of the anti-Chinese policies introduced in four Australian colonies (New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia) from the 1880s, and then in the Commonwealth of Australia from 1904 and the Dominion of New Zealand from 1908. Before these prohibitions, however, thousands of Chinese men in Australia and New Zealand became British subjects through naturalisation, nearly 1000 in New South Wales alone. In this paper then I want to think about the legacies of this earlier history of colonial naturalisation in the lives of Chinese settlers and their families in the 1890s and after Federation, particularly concerning mobility and residency rights. I will argue that it is through the stories of individual lives, revealed in the press and in government case files, that we can best understand the ways that naturalised Chinese Australians and their children contested discrimination and asserted their rights as citizens.

Naturalisation and Chinese restriction

The first anti-Chinese legislation was introduced in Australia in 1855 in Victoria, followed by a similar Act in South Australia in 1857. New South Wales then followed suit in 1861. With tonnage restrictions and a poll tax on each Chinese arrival, this legislation was effective in reducing the Chinese population in the colonies, and so, having served its purpose, it was repealed: in South Australia in 1861 (after three years), in Victoria in 1865 (after 10 years) and in New South Wales in 1867 (after 5 years). Between then and 1881, there was no restrictive legislation against Chinese immigration – except in Queensland, which introduced a Chinese Immigration Restriction Act in 1877. In 1881, however, new and more consistent legislation was introduced across the colonies after the 1880–81 intercolonial conferences. This legislation was then tightened following the Intercolonial Conference on the Chinese Question in mid-1888. Laws varied slightly across the seven colonies, but they generally had tonnage restrictions and some a poll tax to limit the number of Chinese migrants. They also included various exemptions, for residents and British subjects.

In New South Wales, Victoria and New Zealand, for instance, the 1881 Acts brought in a £10 poll tax on Chinese arriving by sea or by land and a limit of one Chinese to every 100 tons of shipping. The NSW and Victorian Acts exempted British subjects, while in New South Wales and New Zealand, other Chinese residents could also apply for exemption certificates. In 1888, the tonnage limits increased in each of these colonies, and the NSW poll tax leapt to £100, while it was abolished in Victoria. Each colony exempted Chinese naturalised in that colony, while the NSW Act also explicitly exempted British subjects by birth. Significantly, too, the NSW Act prohibited the naturalisation of Chinese. After Federation, the Australian colonial laws were repealed, although not immediately – in New South Wales, for example, the poll tax remained in place until 1903. The new federal Immigration Restriction Act, which came into force from the beginning of 1902, provided exemptions for those who had formerly been domiciled in the Commonwealth or in any colony which had become a state (s 3n). Australian birth and naturalisation certificates could be used as proof of this domicile, although exemption certificates were also issued.

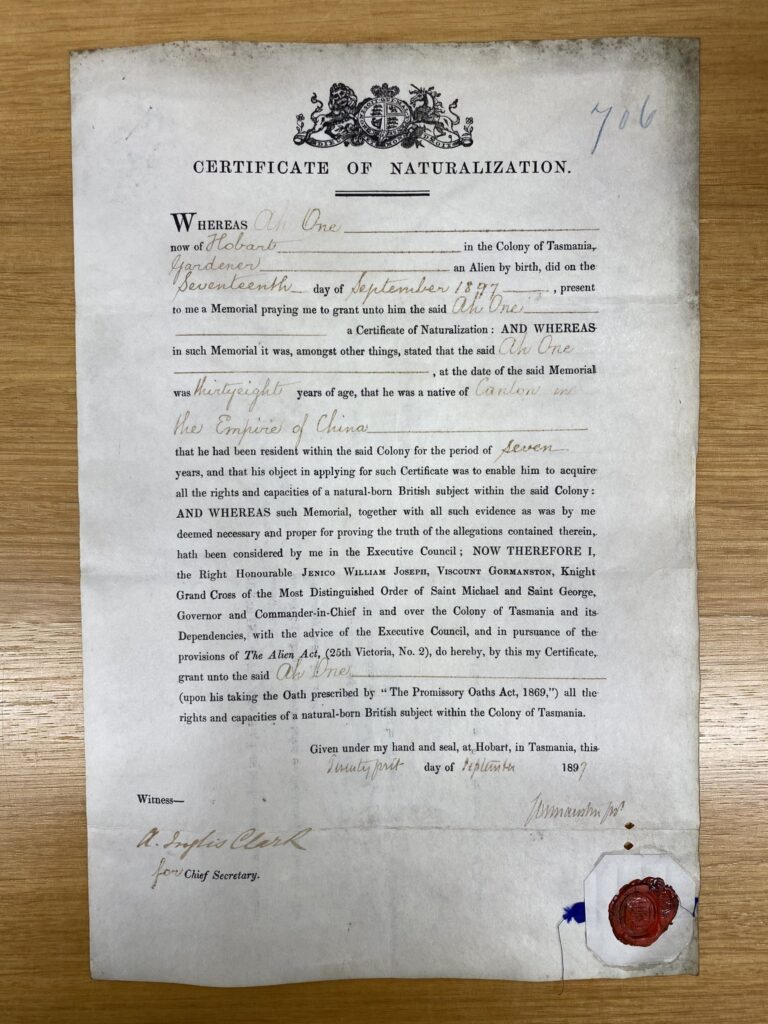

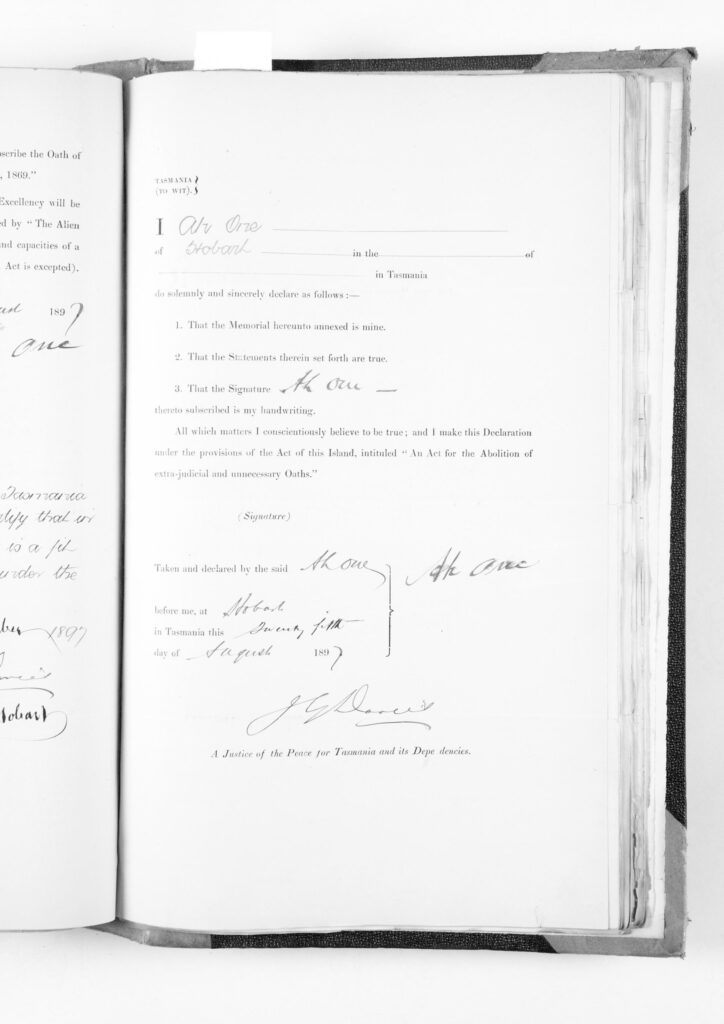

As mentioned, prohibition of Chinese naturalisation also formed part of the anti-Chinese measures introduced in Australia and New Zealand. New South Wales was the only colony that prohibited Chinese naturalisation by law and it did so twice, in 1861 (repealed in 1867) and again in 1888. Three other colonies (Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia) stopped naturalising Chinese after 1888, while Tasmania and Queensland continued until the federal Naturalization Act came into force in 1904. This new Act prohibited naturalisation of ‘aboriginal natives’ of Asia, Africa and the islands of the Pacific, except New Zealand. In New Zealand, Chinese were naturalised until 1907; and it was stopped after the NZ Cabinet decided in February 1908 to decline naturalisation applications of Chinese from them on.

Colonial Chinese naturalisation

The numbers of Chinese who became naturalised in each colony varied greatly, from about 20 in Western Australia up to nearly 3000 in Victoria. In New Zealand there were around 450. As part of my current project, I am compiling databases of Chinese who became naturalised in New South Wales, New Zealand and British Columbia in Canada. If we look at Chinese naturalisations in New South Wales each year from the late 1850s, when the first one took place, to 1888, when Chinese naturalisation was prohibited for the second time, we can see a gap during the 1860s when it was prohibited the first time, and a very obvious peak in the early 1880s. The highest point on that peak is in 1883, when there were 301 naturalisations of Chinese, making up almost a third of the total for the colony. If we think back to what else was happening in the early 1880s, it is clear that this increase was in response to the 1881 NSW Influx of Chinese Restriction Act – which provided exemptions from the £10 poll tax for Chinese naturalised in the colony.

Applicants for naturalisation in New South Wales were asked to state a reason why they sought naturalisation, and most Chinese stated that it was because they wanted to purchase land, or because they had settled in the colony, or something similar. But eight men stated that they sought naturalisation for the rights of ingress and egress. One of these men, Ah Hi, who was naturalised in 1886, stated, for example, that he was ‘desirous of seeing his parents and relatives & returning to this colony where he has an interest in a market garden’. Although there were only a handful of men who explicity stated they sought naturalisation so they could travel across colonial borders, the rapid increase in numbers of naturalisations after the 1881 Act came into force suggests that mobility was a prime motivation.

Other evidence in the archives also shows that Chinese actively used naturalisation to faciliate mobility, for themselves and for their families. There are, for example, Customs statistics that record the numbers of Chinese entering the colonies using naturalisation certificates, reports of individual cases in the newspapers, and Customs and External Affairs / Internal Affairs files that document the travels of Chinese Australians and Chinese New Zealanders. I want now to turn to some of the individual cases of naturalised Chinese and their families – to consider the ways they used their status as British subjects to negotiate anti-Chinese immigration laws, and also to consider the ambiguous nature of the interpretation and application of those laws.

At the borders

So, to return to the Ah Ket children briefly. Under the NSW 1888 Act, any Chinese who produced satisfactory evidence that they were a British subject by birth was to be allowed to enter the colony, yet the Sub-Collector turned the children away for not having naturalisation papers. Would the situation have been different if Matilda, William, Alberta and Ada had produced their Victorian birth certificates, as many Australian-born Chinese did when they returned by sea? Or what if their father was naturalised and they had produced his naturalisation certificate? Would that have been enough proof?

For Chinese Australians, crossing colonial and later national borders was first contingent on being satisfactorily identified, of convincing officials at the border that you were who you said you were. It was then further contingent on bureaucratic and legal interpretations of the law. Each time the law changed, or new regulations were issued, Customs officers at both sea and land borders had to work out how the new policies worked in practice. In her history of the Chinese in Sydney, Shirley Fitzgerald has noted, for example, that in the early 1880s, administering the 1881 Chinese Restriction Act took up much of the Collector of Customs’ time and energy, and he regularly complained to his superiors that he had inadequate staff to deal with incoming and outgoing Chinese (Shirley Fitzgerald, Red Tape, Gold Scissors, pp. 28–29).

Each time the law changed, Chinese Australians also had to work out what the new requirements meant, and how they could best negotiate them, whether by lawful or unlawful means. The dramatic increase in Chinese naturalisations after the 1881 Act is an example of this, and so too is the fact that by 1885, the Sydney Collector of Customs believed that there was a solid trade in naturalisation certificates, which were ‘sent to China and sold’. Chinese Australians made use of their rights where and how they could, and pushed back where and how they could, particularly where the law left room for negotiation.

Family mobility

Naturalisation allowed Chinese men themselves to come and go from Australia and New Zealand, but it also facilitated the entry of their wives and children. In 1898, Nicholas Lockyer, the NSW Collector of Customs, told Sydney’s Evening News that two ways that Chinese evaded the poll tax were by ‘the transfer of naturalisation papers’ and by ‘Chinese women passing themselves off as wives of men who have been formally naturalised in New South Wales’. Such suspicions resulted in careful investigations and meticulous recordkeeping, particularly after the turn of the century.

One example is the Ah Lum family of Sydney. Mrs Ah Lum (I’m afraid that I haven’t yet identified the names of some of these wives and children) came out to live with her husband in 1895. He was a storekeeper and had been naturalised in 1882, returning to China to visit a few years later. The Ah Lums’ daughter was born in 1887, after Ah Lum had returned to New South Wales, and she had stayed in China with her grandmother after her mother migrated. In 1899, Ah Lum asked for permission for his daughter to come to live with him and his wife, as his mother had died and the child had no one to care for her. After some investigations by the Customs department’s Chinese inspector, a permit was issued so Ah Lum’s daughter could enter without paying the poll tax.

The Ah Lums’ case was a relatively straightforward one, unlike that of George Lee’s family a few years later. Lee had been naturalised in 1884 and returned to China not long after to be married. In August 1902, he brought his wife and two sons, Quong Foo and Quong Jah, to Sydney. Mrs Lee was admitted without question because she was the wife of a naturalised British subject (and a wife’s nationality followed that of her husband), but officials demanded the £100 poll tax be paid for each son. Lee paid up, under protest, and the Presbyterian Church raised the matter with the Premier and Solicitor-General on his behalf. They were told that Lee was only a British subject while in New South Wales and that as soon as he left, he reverted to Chinese nationality, hence his children were not British subjects by birth or descent. When asked about the matter, Prime Minister Edmund Barton stated it was not of his concern – the payment of the poll tax was a matter for the state of New South Wales to decide, and the family had been allowed in properly under the Commonwealth Immigration Restriction Act.

Barton could be so dismissive of his responsibility because, at that moment in time, domiciled Chinese men were able to bring in their wives and minor children under section 3 paragraph m of the Immigration Restriction Act. This provision was suspended by proclamation after only 15 months, and repealed in 1905, but during the time it was in force 88 Chinese family members, mainly wives, were allowed to enter Australia permanently. One of these was the wife of Kok Say, managing partner of the Hong Yuen & Co. store in Inverell. In mid 1902, Kok Say wrote to the government requesting a permit for his wife’s entry and stating his credentials – he had been naturalised in 1884 after arriving in the colony of New South Wales nine years earlier. In his words, ‘I have made my home here & have no intention of returning at any time to China’. His request was granted without issue and Mrs Kok Say arrived at Sydney from Hong Kong in November 1902.

After the repeal of section 3 paragraph m in 1905, the entry of Chinese wives and children was solely at the discretion of the Minister for External Affairs, and over the following years we see naturalised Chinese continuing to try to find ways to bring their families to Australia, including through legal challenges in the courts. In New Zealand, naturalised Chinese similarly tested the limits of the law in their efforts to bring out wives and children without having to pay the poll tax, which continued to be applied until 1934, before finally being repealed in 1944.

Conclusion

Although the prohibition of Chinese naturalisation was part of the suite of anti-Chinese measures introduced in the Australasian colonies from the 1860s through into the 20th century, its history is more than one of simple exclusion. It is important to also consider the times when Chinese could be, and were, naturalised, and the ongoing legacies of this in their and their families lives. As British subjects, naturalised Chinese had legal and political rights that they continually asserted, testing and challenging the limits of policy and law. Sometimes they were successful in these challenges, sometimes they weren’t, but when we look closely at their individual cases we can see how their actions both shaped and were shaped by the law. We can also see inconsistencies and ambiguities in the law and in the ways it was administered and applied.