The village of Shiquli in Luokeng, Xinhui (新會區羅坑鎮和平村石渠里) sits at the heart of one of my ongoing research projects. Victorian-born James Minahan (1876-?) spent more than twenty-five years in Shiquli, from the age of about five to thirty-one, when he returned to Australia. Arrested as a prohibited immigrant after failing the Dictation Test on his arrival in early 1908, his case proceeded to the High Court (Potter v. Minahan 1908) and he was eventually granted permission to stay in Australia. Whether he did or not I still don’t know, even after exhausting every lead I have found in the archives in Australia and now visiting Shiquli for a third time.

While I might not yet have uncovered James Minahan’s fate, I have discovered that the tiny village of Shiquli sent dozens of men to Australia from the 1860s into the twentieth century. The earliest were gold-miners, with some becoming storekeepers, but many in later years were simply gardeners. While I was in Shiquli last Saturday, we found a poignant piece of material heritage that reflects this history.

Stashed away in a shed next to one of the few huaqiao houses in the village — the house of Chen Zhidian 陳稙典 (pronounced Tsun Zek Din in Xinhui dialect), built on his return to the village in 1948 (22°27’08.14″N 112°55’47.93″E) — was an old shovel that was said to have been brought back from Australia many years before. Once the dirt and a bit of the rust was cleaned off, I could just make out the words SAVAGE and SYDNEY underneath an insignia of a six-pointed star in a circle. Bingo!

The shovel has now been acquired by the fine gentlemen of the Kong Chew Chan Clan Culture Research Association (岡州陳氏文化研究會), with whom I was visiting the village, who plan to treasure it appropriately. I promised to find out what I could about the shovel’s origins, so this post is a brief outline of what I’ve been able to find out online from China (honestly, what would we do without Trove?).

W. Savage & Co., the manufacturers of the shovel, were originally based in Newcastle, New South Wales. In 1926, a notice was published in Sydney’s Daily Commercial News that a new company, W. Savage & Co., had been registered to acquire the business of W. Savage & Co. at Newcastle. The company were wholesale and retail storekeepers, general merchants, ironmongers and engineers (Daily Commercial News, 12 January 1926). In the late 1920s the company was the Newcastle agent for a range of building and hardware products and machinery, including:

- Armstrong-Holland hot mixing plants for road construction (Newcastle Sun, 1 March 1926, 19 August 1929)

- Bitumastic anti-corrosive paints (Newcastle Sun, 1 December 1924, 16 February 1927, 1 April 1929)

- Cameron and Sutherland pumps, compressors and boilers (Newcastle Sun, 26 February 1926)

- Cyclone woven fences and metal gates (Newcastle Sun, 2 June 1929).

W. Savage & Co.’s involvement in shovel manufacturing began in mid-1928 when they set up a new factory at their premises in Parry Street, Cook’s Hill, Newcastle (Newcastle Sun, 2 July 1928).

A Mr Gaythwaite, ‘an experienced shovel-maker from Cumberland, England’ had, a number of years earlier, come up with a new design for a shovel which he patented under the name ‘Gaylac’. The shovel had corrugations on either side of the handle that were said to strengthen the shovel across the back of the blade and counteract leverage stress. Gaythwaite began manufacturing the shovels in partnership with a Mr Black in around 1926, just in their spare time, and distributing them in the Cessnock and Kurri Kurri districts in the Hunter Valley.

The shovels proved very popular and so Gaythwaite and Black went into partnership with W. Savage & Co. By 1929 ‘Gaylac-Star’ shovels featured prominently in W. Savage & Co.’s advertising (Newcastle Sun, 5 August 1929).

The shovels were made in Australia from entirely Australian materials — the billets were made by BHP and rolled by Lysaght’s into sheets from which the shovels were cut. They were then pressed into shape with a machine, tempered in an oil bath, and set and balanced by hand.

By the end of 1931, W. Savage & Co. was based in Sydney. In December that year they were in court arguing over the rent they could charge for the commercial premises they still owned in Parry Street, Newcastle (Newcastle Morning Herald, 23 December 1931). These premises had been for sale in mid-1930 and it seems likely that this was when W. Savage & Co. relocated to Sydney. The business was one of several in Parry Street that were broken into in August 1929 (Newcastle Sun, 24 August 1929), at which time a safe in the W. Savage & Co. offices was blown open and cash and a cheque were stolen.

W. Savage & Co.’s move to Sydney came around the time of the Great Depression (1929-1932), and it seems that it was after the difficult times of the depression that things took off. There aren’t any advertisements or articles about the company in the newspapers between 1929 and 1932.

In 1932 council granted permission for W. Savage & Co. to erect a new brick factory to manufacture shovels in George Street, Erskineville (Sydney Morning Herald, 6 December 1932).

In 1934 and 1935, Savage & Co. appeared before the Industrial Commission in a dispute over wages for two ironmongers they employed to manufacture shovels using a ‘specialised process’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 27 September 1924, 26 February 1935, 27 February 1935).

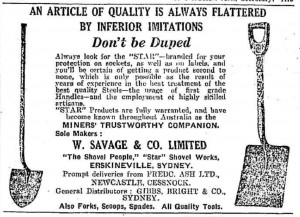

By the mid-1930s, the shovels were no longer being advertised as ‘Gaylac-Star’ shovels, but simply as ‘Star’ shovels, part of an expanding range of ‘Star’ products that included forks, scoops and spades. Their high quality was said to come from ‘years of experience in the heat treatment of the best quality Steels — the usage of first grade Handles — and the employment of highly skilled artisans’ (Newcastle Morning Herald, 12 October 1935).

In 1940 a fire broke out in the George Street factory caused by a burst oil pipe leading to the furnace. Twelve employees escaped from the fire, but overhead pulleys and other machinery were damaged (Sydney Morning Herald, 18 October 1940).

Export manifests show that W. Savage & Co. were exporting their shovels in the 1930s and 1940s to places as diverse as Papeete, Calcutta and Suva (Daily Commercial News, 25 January 1936, 12 June 1946, 30 December 1948).

Advertisements from newspapers around Australia show that Star shovels were sold in Western Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory from the early 1930s to the early 1950s (Western Mail, 16 November 1939; Mercury, 3 September 1942; Argus, 2 August 1932; Northern Star, 20 August 1951; Central Queensland Herald, 1 September 1938; Queensland Times, 11 April 1953; Northern Standard, 15 April 1938).

The National Museum of Australia in Canberra has a Star shovel in its collection. It is part of the Claude Dunshea collection (who seems to have been a miner, judging from other items of his in the museum’s collection). The museum’s shovel has a very short handle, while the one in Shiquli has a long handle as shown in the 1930s advertisements.