In this post, I tell the story of the boy whose handprint became an emblem for the Everyday Heritage project. The post was originally published on the Everyday Heritage website on 9 July 2024.

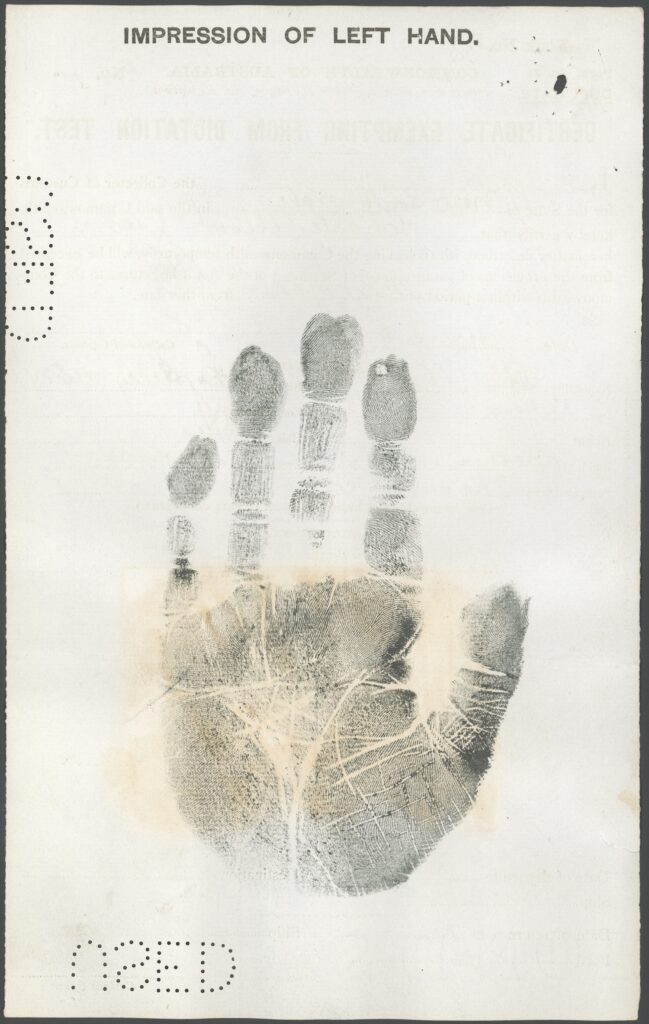

This handprint belongs to a 12-year-old boy called Charles Albert Allen.

Charlie, as he was known, was born in Surry Hills, Sydney, in 1896. His mother was Frances Allen, his father Charlie Gum.

Charlie was raised by his mother, but in 1909, at the age of 13, he was taken ‘home’ to China by his father.

Charlie Gum returned to Sydney soon after, leaving his son in China. Young Charlie lived with relatives in the Cantonese village of Chuk Sau Yuen for 6 years.

Charlie was homesick, but he had no means of getting back to Australia. His mother attempted to enlist the help of the Australian Government but to no avail.

Charlie finally returned in 1915 at the age of 18.

The following year Charlie enlisted in First AIF, the first of three attempts to serve his country. He was discharged as medically unfit each time.

Charlie married Maud Gordon in Surry Hills in 1917, and they had two daughters soon after. Charlie returned to China in 1922 for 7 months.

Charlie Allen died in 1938 as the result of an industrial accident at the Bunnerong Power Station where he worked. He was 41.

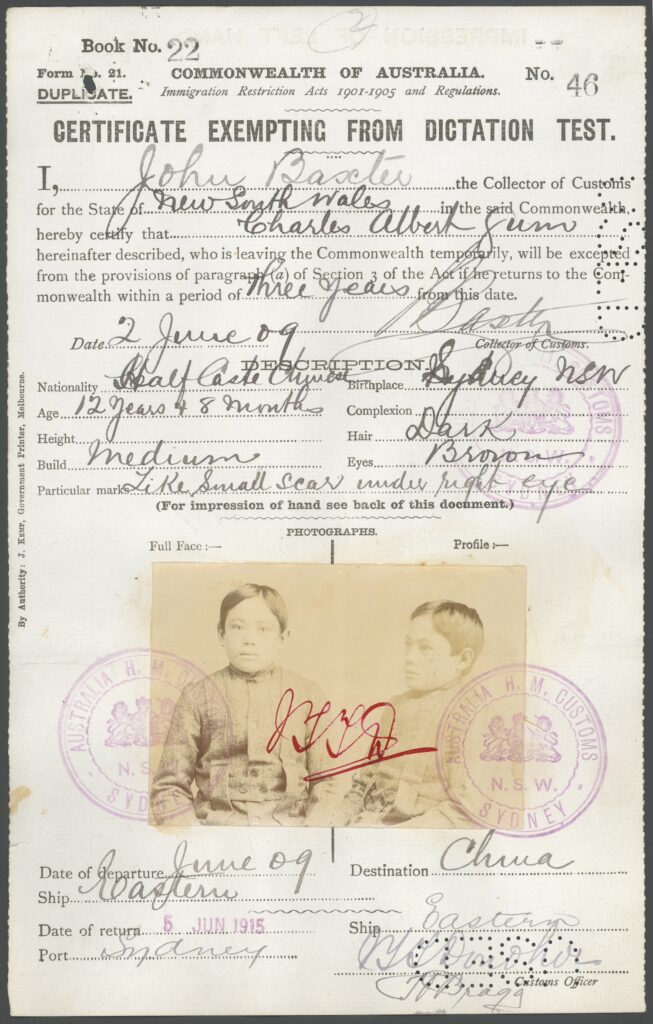

Charlie Allen’s handprint is found on the back of an identification document called a Certificate Exempting from the Dictation Test.

The certificate was issued by the New South Wales Collector of Customs in 1909 under Australia’s infamous Immigration Restriction Act. Today it is held in the National Archives of Australia in Sydney.

Charlie’s certificate, with its photographs and handprint, is one of tens of thousands of similar documents that were issued to ‘non-white’ Australians when they travelled overseas in the early twentieth century. These certificates allowed them to return home to Australia without sitting the infamous Dictation Test.

Every one of these certificates could be used to tell a story of how the everyday lives of Australian were affected by the White Australia Policy.

Among these many possibilities, the story of Charlie and his mother, Frances, particularly struck me, and I’ve written about them in an article that draws on methodologies of biography, microhistory, and family history. As well as his 1909 CEDT, the files in the archives include photographs of Charlie, and handwritten letters from him to his mother and from his mother to the Australian Government.

Charlie’s letters home from China are particularly significant. They provide a rare glimpse into the experiences and emotions of an Australian boy living in his own migrant father’s homeland. While many hundreds of young Australians of Chinese descent spent time in China across the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, first-hand accounts like Charlie’s are rare.

In 1910 Charlie was homesick and a long way from home. ‘Every minute I think of you, and long for a piece of bread and butter this tucker is not doing me well’, he wrote to his mother, before signing off with a flurry of kisses.

In 1911 Florence was missing her son dearly but was unable to get him back. In a letter to the Australian Government, she wrote: ‘Try and do your best to get my son returned back, to me, to Australia … do your best for his mother as I am nearly heart broken about him’.

Beyond the National Archives, I was able to trace the lives of Charlie and his parents, his wife and his children, piecing together fragments of their stories from written records – including birth, death and marriage records; shipping records; war service records; and newspapers – and visiting places significant to their lives, such as Chuk Sau Yuen village where Charlie lived in China, and his grave in Botany Cemetery.

Charlie Allen’s is one of the many ‘small lives’ that can be found in the archives. Telling the stories of lives like his – which are both ordinary and extraordinary – works to counteract dominant narratives – of who belongs and who matters – that continue in our nation’s history and heritage today.

These stories also touch the lives of everyday Australians. Charlie’s great grandson recently told me that memory of Charlie had almost faded within his family. But, having found the archival paper trail and my writing about Charlie’s life, they could now work keep his memory alive.

Further reading

Kate Bagnall, ‘Charlie Allen’s mystery aunt’, The Tiger’s Mouth (blog), 5 January 2021, https://chineseaustralia.org/charlie-allens-mystery-aunt/.

Kate Bagnall, ‘Writing home from China: Charles Allen’s transnational childhood’, in Paul Longley Arthur (ed.), Migrant Lives: Australian Culture, Society and Identity, Anthem Press, London, 2017. Open access version available at: https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.10846849.

Kate Bagnall, ‘Anglo-Chinese and the politics of overseas travel from New South Wales, 1898 to 1925’, in Sophie Couchman and Kate Bagnall (eds), Chinese Australians: Politics, Engagement and Resistance, Brill, Leiden, 2015. Open access version available at: https://chineseaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Bagnall_Anglo-Chinese-and-the-Politics-of-Overseas-Travel_Chapter-7.pdf.

Kate Bagnall, ‘ “I am nearly heartbroken about him”: Stories of Australian mothers’ separation from their “Chinese” children’, History Australia, vol. 1, no. 1, 2003, pp. 30–40. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2003.11828254.

Here’s another amusing CEDT story. Kwong Sue Duk was visiting China with his family. This included processing of the CEDT’s for 3 wives and several children. I haven’t tracked down everyone’s records yet but I am confident about several as the record numbers are sequential. I can imagine the chaos with 12 children, 4 aged five or under, in the office having their handprints taken. The proof of that is that the handprints of two of the five year old’s were mixed up – a fact noted on the documents. The records are NAA: J3136, 1906/150 and NAA: J3136, 1906/151.